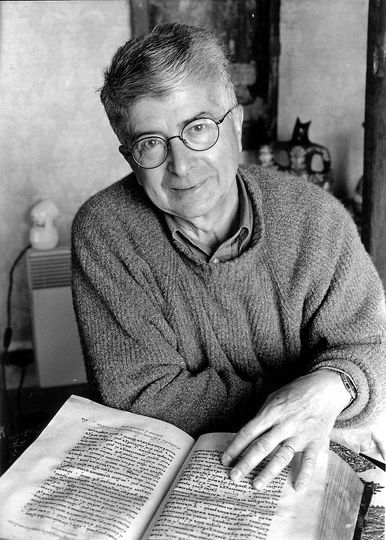

Having just returned from a stay in Russia, where he discovered the Perm region in oriental Ural, Georges Nivat’s eyes sparkle as he talks of his role as collection director for Parisian publisher Fayard. In the inspiring atmosphere of his library, the great Slavist brings us up to date on the new talents of Russian contemporary literature. Speaking of literary production, the honorary University of Geneva professor has not been idle on this front either. In addition to the latest volume in his “History of Russian Literature” series, he is also preparing to publish the first volume of “Sites of the Russian Memory” for Fayard.

How do you explain the fascination that Russia elicits in the majority of its visitors? It’s a cocktail made with a mix of Russian spirit, orthodoxy and a kind of violent artistic explosion. It attracts searching souls, who find in it an answer to life, because Russian life is more fraternal and there is more solidarity. Swiss students who visit Russia are often struck and seduced by the citycountry dichotomy instilled in many Russians, whereby they live in the comfort of the city in winter and spend the summer in primitive datchas without any comfort to speak of, surrounded by deep and immense nature.

Are there enough students studying Russian in Swiss universities? You can’t have a bunch of Slavic armies in Switzerland, it wouldn’t make any sense.

Switzerland doesn’t offer enough opportunities in higher learning, and very few in secondary schools.

Instead, Switzerland must develop Russian as a complimentary avenue for studies in economics, ethnology, political science, sociology, and many other disciplines. The Russian science is immense and students have an interest in learning this language, which offers a view that is both different and European, and in addition presents new employment opportunities. Ever since Russian publishing became completely free, it has flourished extraordinarily. Russia is even ahead of France in terms of books published per year.

According to you, what makes Russo- Swiss relations so special? It’s the intensity of the private relationships. In proportion to its size, Switzerland is the country with the highest number of occurrences in Russian culture.

In Dostoevsky’s “The Idiot”, Prince Mishkin is treated in Switzerland, numerous German-speaking Swiss settlers established themselves in Russia during the reign of Catherine the Great, and French-speaking Swiss such as Frédéric César de la Harpe and Pierre Gilliard worked as advisors for the tsars, to name but a few examples. The complimentary private relationship between this gigantic country on the one hand and this minuscule country on the other is quite striking.

What opportunities are there in the Russian market for the Swiss? Russia has a very qualified workforce; on the other hand, one sometimes finds a lack of continuity in the desire to run things on the side of the Russians.

It’s for this reason that in the 18th century, Catherine II called for settlers from Franconia and Germanspeaking Switzerland. Today, one senses a new call for a type of colonisation, an importation of experts and specialists. This call from Russia represents an exceptional opportunity for Western Europe, and in particular for Switzerland, as proportionally more Swiss are recruited. One mustn’t let this pass by.

If you had to enter into business with Russia, what sector would you choose? Several of my friends have had the experience and have proven that whoever has a bit of an advanced idea can find an extraordinary field in which to realise it in this country. A friend of my daughter’s, Andrew Polson, founded “AFISHA”, a sort of cultural review comprising listings for nights out, movie schedules and restaurants in Moscow. It’s turned into a very nice business, which now has an immense circulation.

And it was the idea of an Englishman who arrived over there and said to himself “something’s missing”. Many businesses are started that way.

You’re a specialist in Russian literature, one of the fields of which Russians are very proud. Your daughter, Anne, is a major reporter and has notably covered the war in Chechnya, one of Russia’s deepest wounds. Are the debates between father and daughter very animated? We don’t have big debates. I’ve given her advice when she’s asked for it, and I followed her perilous adventures in Chechnya and elsewhere. My daughter loves Russia and could get to know it better, she owns a house in the country. For her, Russia served as an initiator to the Muslim world. It’s sometimes forgotten that the country has been a great Muslim power for many centuries. It’s through her Chechen friends that my daughter gained access into that world. After that she met the Muslim society of Central Asia, and then of Afghanistan, where some residents speak Russian because of the Soviet occupation. From there her knowledge of the Muslim world was sufficient to go to Iraq and to Pakistan.

How do you foresee Russia’s evolution after the presidential elections in 2008? I see it as veering towards a stabilisation consisting of a regime of multiple societies and a singular power, that which is in power, faced with a communist opposition which has no chance of acceding to power and a right-wing opposition which can’t manage to unite. With its gigantic territory, Russia can’t have the same federalist system as in Switzerland.

It’s dictated by geography. Russia must have a strong central power to maintain the integrity of its territory, which is to its citizens’ advantage. For that it is necessary that the advantages linked to dependancy on Moscow, from Kaliningrad to Kamchatka, remain. Society seems free to me and I think that the standard of living will continue to rise.

Do you have a favourite Russian author? I have several. First of all Dostoevsky, who’s an author only Russia could produce. One could imagine the other authors coming from elsewhere, however one can’t imagine Dostoevsky coming from anywhere other than Russia. His characters, infused with an existential fever and haunted by the problems of existence, of inexistence, and of guilt, are entirely linked to the Russian soul, to the orthodoxy and to the social strife as well as the history of this country. Then, I would say Andrey Biely, who is in some way the spiritual offspring of Dostoevsky and whom I have often translated. His novel “Petersburg” is a sort of Wagnerian take on Dosteievsky. And finally Boris Pasternak, who played a large part in my life, both personally as well as poetically.

What view do you have of contemporary Russian literature, is it “worthy” of its 19th and 20th century predecessors? Russian literature has again become rich, complex and contradictory. More things are being published today than in 1912-1913, a period in which there were geysers of literature everywhere. I try to keep up with it as much as possible, seeing as I oversee a collection of contemporary prose for Fayard. I’m very interested by what one might call “magic realism”, a sort of Hispano-American realism as practiced by Gabriel Garcia Marques, which can notably be found in the writings of Mark Kharitonov.

What does this role as collection director bring you? I find it fascinating to follow new literature, for which we have no other criteria but personal taste, contrary to the classics where we know that Tolstoy is a great, and we therefore have no need to search through his contemporaries. We forget that Dostoevsky or Mozart created their work among a literary or musical base, and that neither of them was immediately crowned the greatest musician or writer of all time. My work is simultaneously difficult and enriching. I explore, I read around, and then I make my recommendations to the director of Fayard, who makes all of the decisions.

Is there a contemporary Russian author who could be qualified as emblematic of today’s Russia? Maybe Ludmila Petrushevskaya, who writes theatre and prose. Her very compact writings show that the socium is also extremely compact and oppressive.

One could equally cite the name of Ludmila Ulitskaya. For both of these women social reality penetrates their work in a more direct fashion than with other authors, for whom it also penetrates their work, but through a more distorting mirror.

And finally I will cite Valery Popov for “The third breath”, an amazing book that employs a brutal and crude form of literature, full of black humour, yet is not devoid of tenderness.

Who are three Russian authors whom you would recommend to someone wishing to discover contemporary Russian literature? Above all I would recommend Andrey Dmitriev for his very singular charm. His writings are relatively short, but so dense that you have to give yourself several pages to enter into it and not judge after the first paragraph. His writing evokes mirrored diamonds, it’s very specific. His novel “Closed Book” is a good example. I would also recommend Mark Kharitonov and his novel “Lines of Fate or Milashevich's Trunk”, who was our invited guest at the Rilke festival in Sierre (ndlr. in the Swiss cans ton of Valais) in the month of August. Finally, I would recommend Mikhail Shishkin, author of “Ismail’s catch”, and who also lives in Switzerland.

Will the publication of the final volume of your history of Russian literature be a relief for you? Absolutely, I’m not hiding it! In the beginning there were four of us who dreamt up this project, but now the entire enterprise is on my shoulders. The three others don’t deal with it anymore. One, professor Ilya Serman, is now too old, the other, professor Strada is in Venice and is busy with other projects, whereas the third, Efim Etkind, passed away five years ago. This last volume is dedicated to the vertical constants of literature, and also contains a type catch-up on Russian literature from perestroika to the present day. I’m still waiting for around five articles from different authors who don’t have an easy task, and I have to write one more myself.

Which of the country’s historic events has most affected you? I arrived in Russia for my first internship shortly after the Communist Party’s 20th congress, which had taken place in February 1956. Soviet society was still reeling from Khrushchev’s revelations regarding the Stalin personality cult, which had resulted in the great purges and torture. The report, which was never published, was read within the party’s cells. Friends taught me the party’s cell system.

There existed a double information system: the Pravda (editor’s note: The official Communist Party newspaper) and purely oral information given within the cells. I therefore went to a komsomol (editor’s note: official name given to communist youth groups) meeting, where a student of around thirty years old, who was going back to his studies after having been a sailor and a teacher, explained that there were unemployed people in the Soviet Union who were starving to death. These revelations created a great silence. These terms, normally associated with “America, exploiter of the working class” and now being applied to the land of the Soviets, received an instant reaction from a woman activist. Despite the proof which he detained, the disgusted student disappeared and was officially expelled from the university. I don’t know whether he knew what he was doing and what he was risking.

This episode which I lived through is linked to the khrushchevian thawing period; under Stalin the student would never have spoken out in such a manner. After being expelled, he was probably deported.

Where does your love for Russia come from? It came late. At age fifteen I discovered Dostoevsky by reading a Boris de Scheuzer translation of “Demons”. Meeting a white Russian who worked as a bookbinder in Clermont-Ferrand, my city of birth, also stimulated my interest for the country. After finishing my degree in English, as I wasn’t very interested by the English professors of the Sorbonne, I therefore decided to open the door of the neighbouring department, which was that of Slavic languages. I became acquainted with Professor Pierre Pascal. I was immediately taken with this gentleman who resembled a sphinx. He subsequently played a considerable role in the French Slavic culture and his “Journal of Russia”, written in the form of a travel journal about the Russian revolution, is unparalleled. To sum up, my love for Russia results from a deliberate choice to study this culture in university after having finished English.