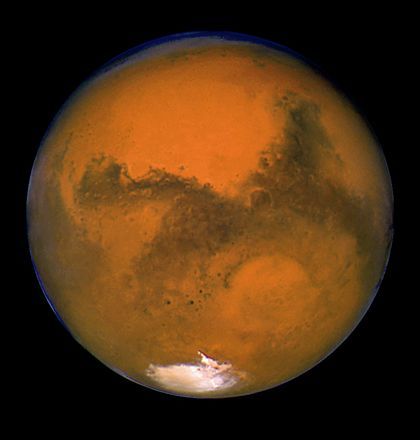

That man will fly to Mars one day is no longer questioned. Even the length of this flight is known for certain – using the optimal trajectory, it will take 350 days one way and as many back, plus 20-30 days to be spent on the planet.

But it is hard to say when it will happen.

Optimists believe that 2017-2018 will be the nearest most favourable “ballistic opening” for a trip to Mars. Pessimists say this timeframe is unfeasible, given that it is necessary to create a spacecraft, its engines and to put the huge apparatus weighing hundreds of tons on a trajectory towards Mars.

Apparently, the Russian Federal Space Agency sides with pessimists, as its head Anatoly Perminov has said recently, “We plan a trip to Mars after 2035.” Nevertheless, work on this project is ongoing as part of the Federal Space Programme. A concept titled “Piloted Expedition to Mars” was drafted in 2005. One of the project’s authors, chief designer with the Keldysh Center, Vitaly Semyonov, said work on the inter-planet expedition project had discovered an important circumstance: the timeframe and cost of the Mars mission are determined mainly by the type of the energy and engine.

Although the technology of existing chemical rocket engines has been perfected, the low maximum rate of combustion products discharge has so far remained a wall that cannot be broken… Oddly enough, it can be passed by. This can be done with the help of rocket engines where the energy source and discharged mass are separated. What can replace ordinary rocket engines? For example, ultralight gases (hydrogen, helium or methane) can be heated and made to flow through the muzzle at a speed that will be 2-2.5 times higher than that of chemical rocket engines.

This can be achieved using either a compact nuclear reactor or a heating element working on solar batteries.

The Soviet Union and the United States actively developed nuclear rocket engines for piloted expeditions to Mars back in the 1960s-1970s, but the work was suspended at the stage of ground tests. Plasma and ion electric reactive engines are even more economical and faster. In them, flow of charged particles is accelerated with the help of an electromagnetic field, almost as in a charged-particle accelerator. The parameter determining their thrust is the power of the unit that creates the field and accelerates particles.

In the early 1960s, American scientists experimented with nuclear reactors equipped with turbine generators, but they faced a problem: the unit was big and not too reliable.

Russia has had a unique experience of creating and using reactor energy units in the outer space. In 1970-1988, it launched a total of 32 spacecraft with nuclear energy units and a thermo-electric transformer with a capacity of 3 and 5 kWh. Most of these spacecraft carried out reconnaissance functions and stayed activated on near-earth orbits for several months. On the contrary, the only US spacecraft with the nuclear reactor SNAP 10A and a thermo-electric transformer with a capacity of about 0.5 kWh was launched in 1965. It worked for only 43 days, but is still on the orbit, now as space garbage. America then made its research on nuclear energy in the outer space purely theoretical and resumed experiments only in 2002.

Russia can also build the so-called stationary plasma engines, with a unit thrust several times higher than that of traditional chemical engines. A unit thrust, i.e. a ratio between thrust and fuel consumption per second, is a crucial characteristic of any rocket engine.

The higher the rate of gas discharge, the higher thrust with the same fuel consumption and, consequently, the more economical the engine. The first SPE was tested in the outer space in 1972, on the Russian meteorological satellite Meteor. Regular exploitation of serial models began in 1982. They were used on geosynchronous satellites to adjust their orbit. At present, almost all countries, including leading space powers, use Russian electric rocket engines on their spacecraft. These engines are so powerful that they can adjust both the longitude and the inclination of the orbit and, moreover, ensure inter-orbit flights along multi-turn trajectories that are best energy-wise, for example, from a low orbit to a geosynchronous one. They can also be used for inter-planet transportation.

When working on the concept of a piloted expedition to Mars, its developers considered liquid rocket engines using oxygen and hydrogen; nuclear engines with liquid hydrogen as the working fluid; nuclear and solar power units for powering electric reactor engines. A solar power unit with thin-film elements based on amorphous silicon was chosen as the basis. However, a nuclear power unit can later be used as well.

At the first stage of the project’s fulfillment, Russia plans to carry out five expeditions using the same inter-planet spacecraft. The expedition complex will also include a solar tow shuttle.

The goal of these expeditions will be to choose and prepare a site for a Martian base. Its dislocation should first of all ensure safety of landing and takeover, the project’s authors believe. It is also important that the terrain can be used to set up a housing complex, notably, to improve its protection from radiation.

The terrain should also comply with requirements for monitoring asteroid and comet dangers for the base’s residents.

Another important issue is presence of liquid water not deep underground.

Finally, analysis of information about Mars’ geological structure has found out areas where there is a small chance of finding traces of life. It is possible that these areas will be the most attractive for deployment of the first extraterrestrial base.

Moreover, the human factor remains the priority in the work on the strategy and plan of a piloted expedition to Mars, while man is the most vulnerable link in the mission, to a large degree determining its plausibility. Medical and biological support to the expedition is a new task set for scientists.

Many principles, methods and means of medical and biological support to orbit piloted flights that have been proved good cannot be used for the Martian mission. The 438-day orbit flight of doctor cosmonaut Valery Polyakov on the Mir station in the late 1990s showed that there are no major medical or biological restrictions for long space missions.

Radiation, however, is a different issue.

Its effect on cosmonauts increases drastically after a spacecraft leaves the magnetosphere of the Earth. This means that a special protection will have to be developed. Perhaps, it will be a bunker made of material that absorbs charged particles or an electromagnetic field artificially created around the spacecraft.

Another problem is food for cosmonauts.

It may seem that this practice has been perfected over years and that the crew will get the same freeze-dried products that are in use today. It is enough to add water and defrost them to have a meal.

Yet no matter how good and tasty these products are, they have to be alternated with more traditional foods.

The idea to breed poultry, notably, quails, in the spaceship so that crewmembers could eat their eggs has been discarded.

Experiments have shown that hatchlings are unable to adjust to weightlessness.

It is easier with fish and shellfish, but they grow too slowly, so cosmonauts are unlikely to eat fresh fish on their way to Mars. One thing is certain, though: there will be a greenhouse on board the spaceship, even if a small one.

Researches at the Moscow-based Institute of Medical and Biological Problems have made a prototype of the space greenhouse. It is a cylinder with a bunch of rollers soaked in fertilisers inside. Its inside is covered with hundreds of red and blue diodes acting as solar rays.

The rollers turn as plants grow, bringing their tops closer to the source of light and thus ensuring an uninterrupted cycle: while plants are only sprouting on some of the rollers, others can already be harvested.

Apart from providing food, the space farm will help to solve the problem of air regeneration on board. However, it is still unclear how space radiation affects plants. The Institute has been engaged in experiments of growing plants in conditions of a space flight since the 1990s, and its research shows that such plants are almost the same as those grown in the ordinary way.

Then there is a problem of water. A cosmonaut needs 2.5 l of water a day, which means there must be several tons on board. Part of water will be recovered with the help of the regeneration system.

The ideal variant would be to create closed-loop physical and chemical systems that would ensure a full cycle of substance. But this seems to be a matter of the distant future.

There are psychological tasks as well.

Due to the great distance, a radio signal will travel 20-30 minutes each way. This means that the mission control center will not be able to interfere in case of a contingency. It will act as a consultant at best, while the decision-making will be transferred to the spaceship. Before the expedition is launched, scientists will try to resolve many of these problems in the Mars 500 mission.

It will be a very accurate imitation of a flight: six crewmembers will spend 520 days in a ground complex consisting of five hermetically sealed connected modules. One of them will imitate the surface of Mars. The modules are staffed with devices registering all kinds of parameters inside and medical parameters of the test persons. It will be important for scientists to see how a team acts in a situation close to a contingency. All results, from their diet to evolution of relations, will be analysed by experts. The experiment will involve six people, although the crew on the real expedition will comprise only four.

Remarkably, soon after Russia announced its Mars 500 experiment, the US also began looking for volunteers for an imitation flight. They will spend four months on the flight. The European Space Agency is working on its own concept of an expedition to Mars, so far without men. China also has plans to land on the planet. So we are in for a new space race. The question is, why flying to Mars at all? Most scientific achievements in the outer space are related to machines, not piloted flights, said Lev Zeleny, director of the Institute of Space Research of the Russian Academy of Sciences. However, man will definitely land on Mars, even if it is completely senseless, he adds. The feelings of a person walking on another planet are invaluable.