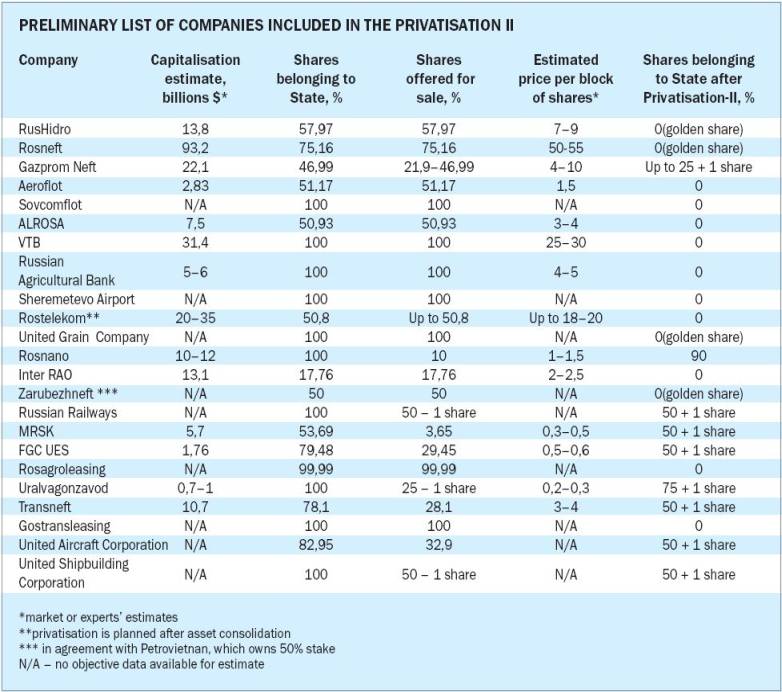

This sort of control isn’t necessary at this time In 2012–2013, the Russian government is hence aiming to relinquish its majority ownership in a number of key businesses, including some renowned banks and companies such as SCF (Sovcomflot), Aeroflot, RusHydro, Alrosa, Rosneft, Gazprom Neft, VTB and the Russian Agricultural Bank (Rosselkhozbank). The new policy will likewise concern telecommunications along with a range of other sectors. As it stands outlined by the government in documents on its large-scale privatisation plan, “it will improve corporate governance and generate private investment in development”. According to Presidential aide Arkady Dvorkovich, who was the first to present the newest large-scale privatisation plan, “The State doesn’t need to have majority ownership in competitive companies. In the long term, it is necessary to reduce the presence of the State to zero, since it is good for the companies themselves”. Should this logic be followed, the privatisation process will obviously be implemented more assertively than was previously expected.

The next scheduled phase of Privatisation II will be marked by the Russian government’s relinquishment of control over sizeable blocks of shares from monopolies such as the Russian Railways (RzhD), the Federal Grid Company (FGC UES), Interregional Distribution Grid Company (MRSK), Zarubezhneft, Transneft, Uralvagonzavod, Rosagroleasing Company and the State Transport Leasing Company. In the long term, within the next 4–5 years and possibly longer, Privatisation II entails the State’s transferring substantial holdings of shares in what were once untouchable public corporations. This move suggests that the plan’s objective mainly lies in attracting foreign investors, for whom it is currently extremely difficult or even impossible to gain access to most of the companies that are intended to be privatised. However, the division of Privatisation II in phases as well as its classification as the second stage of converting the Russian economy to a market economy is extremely conditional.

One must keep in mind that privatisation in Russia has been going on continuously since the 1990s. The two major Russian stock exchanges – the MICEX and RTS – have constantly expanded their lists of traded companies and likewise the number of players has been regularly increasing, largely due to the arrival of foreign participants in the risky but rapidly growing Russian market. Revenue has also steadily increased. But all this has by no means happened at the same pace that even other BRICS countries have been able to achieve. The greater majority of the banking sector, whole-sale and retail trade, virtually every construction business, the vast majority of defence companies and practically all of Russia’s medium and small-sized businesses continue to operate without being traded on the stock market. A quick review of recent historical events is necessary in order to appraise the breadth of Privatisation II and understand the logic guiding the Russian authorities who have been coming to it for so long. The Russian economy’s privatisation began in 1992 with the establishment of a lot of socalled Privatisation Funds which were responsible for Privatisation I’s initial stages. At the suggestion of the then head of the Committee for State Property Management of Russia, Anatoly Chubais, most Russians didn’t actually receive any company shares but were rather given securities in particular privatisation funds. In fact, very few leading Russian companies exchanged these securities of ‘questionable’ value for their own shares.

However, those few Russians who were able to find ways to effectively use vouchers or receipts from privatisation funds could eventually bring in some revenue and occasionally generate a good income. There were even those who actually became rich on vouchers, stockpiling them despite all the bureaucratic obstacles at companies such as Gazprom, Sberbank of Russia, or MGTS – but these cases are exceptions that prove the rule. The overwhelming majority of Russian citizens either simply sold their vouchers right away and neither received any dividends nor the compensation they deserved. Soon afterwards, the notoriously infamous ‘loans-forshares phase’ of privatisation – when State control was withdrawn from leading national commodities companies – began. Moreover, one could take over the State’s shares of a business for a very modest sum. For example, the majority ownership of the world’s leading non-ferrous metallurgy, Norilsk Nickel, cost current owner Vladimir Potanin a total of just US$170 million. Although Mikhail Khodorkovsky is currently in prison, he led the highly aggressive Menatep business group 15 years ago and paid only US$ 130 million for the right to run Russia’s oil giant, Yukos.

The next wave of large-scale privatisations cannot be viewed as a separate transferral of State-owned stakes in businesses to private ownership as they are so obviously a new way of developing the concept of Privatisation I. These were likewise sullied by scandals although they were admittedly less marked than those surrounding the loans-for-shares stage of Privatisation I. In this case, it was yet again the blatant under-valuation of public assets that was at the heart of the issue. Reputed economic analyst Vladislav Inozemtsev cites the privatisation of companies such as Slavneft in 1997, Tyumen Oil Company in 1999, the Eastern Oil Company in 2002 as well as various local energy network companies in the second half of the 2000s as cases in point. Inozemtsev – along with many other economic experts – believes that this happened because Russian privatisation did not pursue economic aims but was determined by political motivations. These factors went beyond the simple desire to destroy an old system and keep a new one in power. The grasping – but understandable – inclination on the part of those involved in the privatisation process to acquire wealth is also a major factor in the equation.

Be that as it may, Russia has succeeded in creating conditions that are relatively similar to those of a market economy. But it has become a caricature of various foreign commodities economies, aside from the fact that it has but a very slim chance of achieving real modernisation. This despite Russia’s satisfactory industrial and scientific structure along with the nation’s highly qualified workforce, which has chosen to remain in Russia. One notes the presence of an opinion – which is particularly characteristic of opposition factions in the Russian State Duma – that the transfer of ownership to private hands has not led to significant business efficiency gains and did not generate a real spirit of competition between the private and public sectors. Moreover, many still believe that privatisation had a disastrous effect on the country’s economy. This can generally be considered a fair evaluation of the situation in light of the fact that many valuable assets priced well below their real value passed into the hands of owners from the private sector. However, the idea that the early years of privatisation led to parts of businesses having to be sold or simply closed down does not hold water. It is namely the transparently and more or less legitimately privatised enterprises that are currently leading the Russian economy, and many so-called State-owned enterprises have either been eliminated or sunk to the status of third rate players.

The script remains to be written

The script remains to be written There are obvious reasons why the Russian government is choosing to implement a privatisation policy at this point in time. Namely the pressing need to reduce corruption and shady business practices. However, the State still has no intention of removing itself from companies and sectors where there is minimal competition in terms of infrastructure and government control is not a serious obstacle to efficient business operations and investment appeal. In light of the current pre-electoral period in Russia, it’s highly significant that the latest privatisation initiatives are being actively supported by both the Presidential Administration and the White House – the heart of Russia’s government. But virtually every major political – and particularly economic – event in Russia is now viewed in terms of the upcoming electoral presidential race. However, Privatisation II’s parameters still more or less fit into a plan to modernise Russia’s economy rather than reflecting the traditionally conservative attitude on the matter.

The main evidence for such an assessment lies in the introduction to the longterm privatisation list of three public corporations created in the 2000s as a parallel to Korean chaebols – Rostekhnologii, United Shipbuilding Corporation and United Aircraft Corporation. When these Russian versions of Korean chaebols were created, government-owned corporations were practically regarded as the universal panacea for increasing efficiency in industries where direct privatisation was considered either unpromising or simply impossible due to strategic considerations. The reorganisation and even the transferral of most partially State-owned corporations – many of which still lack a stable organisational structure – to stock exchange traded status may become the main component of Russia’s Privatisation II. Rosano’s efficient transition to a joint-stock company with 100% government stake is a revealing example. Rosano is now being headed by Anatoly Chubais, who both instigated and organised Russia’s Privatisation I.

A new and complete privatisation plan has yet to be definitively laid out but is constantly expanding as it’s being prepared. Therefore, the second list which appeared on August 1 – the date set by President Medvedev to make ‘radical proposals’ – was nearly twice as long as the initial list issued by the White House. If even only the preliminary form of this plan is implemented, it would still largely surpass the scope of Privatisation I. For example, should State revenue not exceed US$ 1 billion (or RUB 30 billion at the current exchange rate) during the loans-forshares auctions, the proceeds generated by privatisation could reach up to RUB 6 trillion in 2012–2016. Earlier assessments of the prospects were much more modest with estimated revenue set at RUB 280–300 billion in 2012, rising to RUB 1 trillion in 2015 and going up to RUB 1.8 trillion in 2016. According to some experts, the constant expansion of the list of companies to be privatised can strongly support the Russian stock market in the long term.

Here yet again, the plans for large-scale privatisation could very logically befit Russia’s plans for modernising economic development. The plans themselves are a testimony to the Russian leadership’s strong commitment to the liberalisation of government – which is viewed by investors as being very positive. Furthermore, increased efficiency of companies that have been privatised as well as direct growth of global market capitalisation are both expected to ensue as a result of the world wide expansion of market capacity and privatised companies’ market capitalisation growth. The number of liquid stocks is due to increase sharply and improve opportunities for investors in terms of both sectoral and regional diversification and will increase Russia’s share in international indexes.

Reconnaissance by attacks But in terms of a preliminary assessment of just how effective Privatisation II could be, one should consider the recent floating of significant shares in Sberbank and VTB (close to 10% for each company) and the placement of Sberbank’s depositary receipts on the London Stock Exchange a ‘reconnaissance by attacks’. Fusing Russia’s two major stock exchanges – the MICEX and RTS – befits the privatisation strategy and is now going forward at full speed. According to some experts, financial ratios of the combined stock exchanges must meet performance indexes comparable to those stock exchanges which are currently leaders within regional developing countries. Alexander Osin, Chief Economist at Finam Management, assesses the potential combined market capital of RTS and MICEX at RUB 200 billion. However, the agreement regarding the merger evaluated the MICEX at RUB 103.5 billion and the RTS at RUB 34.5 billion. However, these estimates do not take into account the potentially vast stock exchange earnings growth in developing countries. This move is due to the movement of financial capital from developed markets, as a result of the increasing government regulation of financial services as well as the growing number of investments in developed stock markets over the next few years that has already been predicted due to the debt market’s recently increased risk.

Fusing the RTS and MICEX is being implemented due to various external factors including the growth of debt and financial risk across the world, the market and State agencies’ desire to reduce these risks, decreased global consumption growth rate and the consolidation of companies from the financial sector. Generally speaking, this fusion is a normal process which enables cost reduction, expanded sales of the new structure’s services as well as preventing hostile takeovers and consolidating its own position on the market by merging with competitors in the Russian financial sector. Alexander Osin is certain that a single platform will strengthen the positions of both stock exchanges by creating a single stock market in the context of global market competitiveness. It is interesting to note that the merger will take place in tandem with the public offering – IPO of one of the stock exchanges, the RTS with the participation in its capital of the Central Bank of Russia (CBR).

According to documents signed in late June 2011, CBR shares on the unified stock exchanges will total to 21–24%. However, these shares may decrease after the IPO, which befits the new privatisation strategy. Unification will accelerate the expansion of the unified stock exchanges in Russia and neighbouring markets. The reduced costs should result in a decreased cost for services, although this will require significantly strengthening anti-monopoly authorities’ control. It remains only to remember that Russia’s plans for privatisation make no mention of Gazprom, which is not surprising. The gas giant has long been a strong presence on the Russian as well as international stock markets. Moreover, as noted by the same Arkady Dvorkovich, “the large infrastructure component” in Gazprom’s activities allows the gas giant to be listed as one of the companies for which privatisation would be deemed inappropriate.