“Russia will become a global food superpower as the same climate change opens up the once frozen and massive Siberian prairie to food production.” The Guardian, 2.1.2011

UNTAPPED RESOURCES

Ensuring the nation’s food supply is every modern state’s strategic objective. This issue goes hand in hand with the world’s population explosion, a considerable percentage of which will occur in Asian countries surrounding the Russian Federation’s borders. Prices for meat, milk and grain are rising all over the world. In 2010, food costs rose by 8.7% in Russia. The fact that the possibilities for increasing the world’s productive land area are limited cannot be ignored either as erosion, swamping, soil salinity, etc. is reducing the planet’s arable soil at a rate of about 10 million hectares every year. Within the next forty years, the Earth’s arable soil resources will decrease by more than 30%. But as Russian territory comprises 9% of the world’s arable land, the nation has the potential to become a major player in supplying food to the global market. The geopolitical importance of Russia’s arable land has long been recognised in Europe – Hitler had good reasons for importing Russian and Ukrainian black soil to Germany. At the present time, rapid climate changes have expanded Russia’s area of arable farming into Eastern Siberia. Russian soil is particularly attractive in terms of ecologically clean agriculture. Whereas the soil in Europe has been depleted by the longterm use of chemical fertilizers, huge areas of fertile soil in Russia were either never exposed to modern fertilizers or lay completely fallow for many years. This is due to various factors, including the economic stagnation which followed the collapse of the Soviet Union. Meanwhile, scientific surveys indicate the human race in general – especially the populations of wealthy countries in Europe, the Persian Gulf and North America – will need much more environmentally friendly products in the near future than they do now. The number of people with particular dietary needs – those who suffer from allergies, diabetes, etc. – is expected to sharply increase all over the world.

Everything indicates that Western countries will inevitably turn to Russia due to the country’s tremendous potential for agribusiness.

So how to find potential ways to increase agricultural production in a country which often suffers from food shortages? First of all, energy and labour costs need to be reduced as expenditure in these areas is several times higher in Russia than it is in developed countries. For example, every person involved in direct agricultural operations in the US during any given year generates a total of almost $70,000, and in Russia the return only comes to $4,000 per farm employee. Unfortunately, Russia’s farmers are far behind in comparison to Asian farmers. Experts estimate that one Chinese agricultural labourer produces a return equivalent to two Tajik and four Russian farm workers. This may lead to substantial changes in Siberia’s ethnic population, as the region will inevitably begin requiring cheap and skilled labourers to migrate from neighbouring China. However, efficiency and productivity can be achieved by increasing yields, which currently stand at just 1850 kg per/ha in Russia whereas the figure is much higher in developed countries (between 5000 and 6000 kg per/ha).

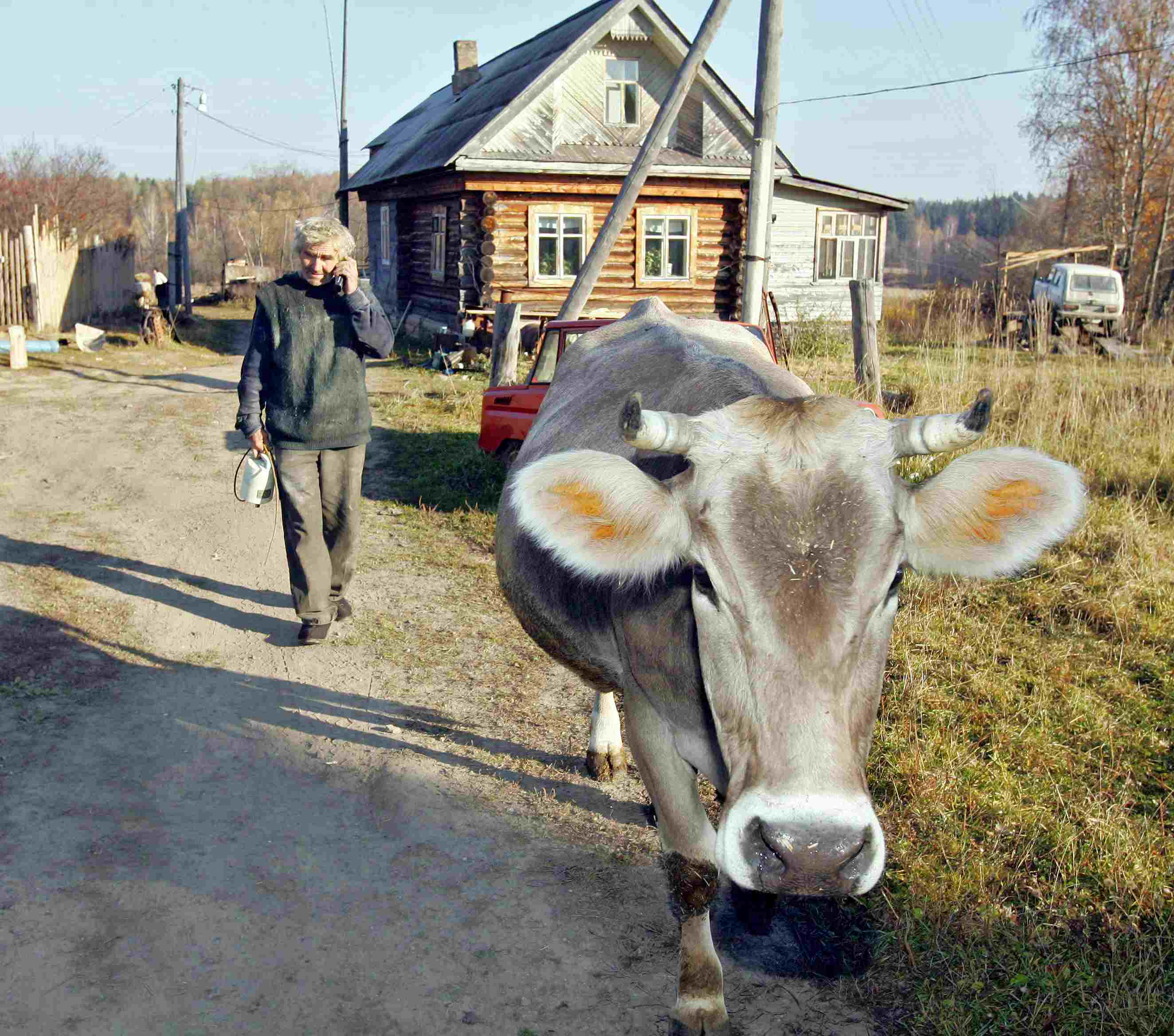

In so far as animal husbandry is concerned, dairy cows in Russia yield an average of 3,300 kg of milk annually although the average return per cow is 8,000 kg per year in EU countries.

Agriculture, as is the case in other sectors of the nation’s economy, urgently needs to be modernised. This is best exemplified by the fact that just 2% of Russia’s arable land is treated with eco friendly technologies, while it has reached over 90% in Canada.

However, in order to exploit these unclaimed resources, many problems need to be solved beforehand – and primarily the continually unresolved issues of land ownership and agricultural machinery, as well as the nation’s rather limited processing capacity need to be addressed. After all, the question of property ownership has bedevilled Russia for many centuries and continues to be problematic. According to industry experts, another key agricultural issue is underdeveloped infrastructure in rural areas, where production is not only difficult to achieve, but also presents a problem in terms of transporting foodstuffs to market in saleable condition.

However, the significant number of successful farming enterprises is a sure indicator of the Russian agro-industry’s enormous growth potential. Over the nearly 100 years that have elapsed since the fall of Tsarist Russia, the country's agriculture has experienced very difficult, controversial challenges and what may be the most dramatic period of development it has ever known. However, history has proved that sound public policy in rural areas can yield significant results. This trend has been confirmed in neighbouring countries such as Finland, Poland, Belarus and the Baltic countries, where climatic conditions are but slightly different from those in Russia. Russia’s main agricultural producers provide another example of the same trend as in the aforementioned countries and the crop yield per growing season in the agricultural sector is potentially so high that it could justify almost any largescale investments.

BREAD ABOVE ALL

The level of Russia’s cultivated areas and crop production fell from the early 1990s through the early 2000s. The negative trend later reversed itself, or at least began to slow down. However, the economic crisis of the late 2000s in conjunction with the drought in Summer, 2010 could seriously hamper the positive developments planned.

The primary agricultural indicator is grain production volume, which is based on crop area and yield. Soil and climatic conditions have a tremendous impact on the production process in terms of labour and costs. In order to accurately assess Russia’s grain production, one must factor in the dynamics of arable land and cultivated areas (see graph below).

Approximately 50–65% of the cereal planted in Russia is wheat. Studies over the past 120 years show that grain production in Russia began to increase after 1945 and that this positive trend continued through the early 1980s. At the end of the 1970s, Russian grain production reached a record high of 130 million tons, whereas the annual average previously stood at about 100 million tons. This figure began to decline in the early 1990s and the downward trend is still continuing, although it is less dramatic now than it was in the past.

There was a small rise in the Russian agricultural sector in 2009, which increased by approximately 1.4%.

However, this figure is expected to drop significantly – by 10% – due to last year's drought and, above all, as a result of technological failures. Although the 2008 crop totaled 108 million tons of grain, this figure had already dropped to 98 million tons in 2009 and went down to 60.5 million tons in 2010.

MORE HIGH QUALITY TRACTORS ARE NEEDED

According to the Ministry of Agriculture, agrarian businesses in Russia currently operate with 520,000 tractors, 160,000 ploughs, 191,300 cultivators and 236,600 seeding machines. Agricultural equipment – tractors, cultivators and seed drills – are traditionally repaired during the Winter season. Technical readiness usually reaches 70–75% by January and 85–90% by April.

Experts from the State Duma’s Agricultural Committee assert that the financial resources required just to purchase spare parts for agricultural equipment total about 20 billion roubles (nearly 500 million euros) nationally per year, and that the cost of purchasing new equipment can reach up to 100 – or even 150 – billion roubles (2.4 – 3.6 billion euros) annually. In this case, we are not talking about coming even close to the level of technical support achieved in the new EU member countries’ rural areas across Central and Eastern Europe.

The previously cited expenditures only serve to provide the Russian agricultural sector with the means to remain within seasonal time constrains which correspond to local climates in terms of crop production (ploughing, seeding, planting and harvesting). Let’s not forget the fact that in Russia’s case, even the best agricultural machinery cannot perform as well as it does in Europe or Canada, primarily due to the nation’s seriously underdeveloped infrastructure.

An important factor which will contribute to increasing agricultural capacity in the future will stem from the worldwide demand for renewable energy. Experts claim that in 2015–2025, renewable energy sources from agricultural raw materials (agro fuels – bio ethanol, methyl ester from rapeseed, biogas) will supply at least 10% of consumer demand. Above all, this provides Russia with the opportunity to realise its agricultural potential and increase bio fuel production volumes from agricultural raw materials such as rapeseed, soybeans, sunflowers and sugar beets. These crops currently account for 7.1% of cultivated land in Russia, whereas just rape crop rotation represents 24% of arable land in Germany and 16% in Poland.

IS THERE AN ALTERNATIVE TO “BUSH LEGS”?

The majority of Russia’s livestock is cattle and poultry. In the reform years of the 1990’s, the fall in animal husbandry was very significant, and is now recovering more slowly than in other areas.

A characteristic feature of Russian animal husbandry over the past two or three years has become the priority placed on developing higher quality production. The reason for this trend is the change in nutritional habits across large sections of the Russian population. Although more than 40% of the population has reduced its meat and dairy consumption and is increasingly turning to starchy foods and vegetables, there has also been a significant part of population that increased (from 4–6% to 8–11%) its meat, dairy and various food products consumption. However, in some regions this sparked more than a change in consumer demand but gave rise to a permanent increase in livestock production. The absence of overly strict regulations in the agricultural sector and the new, active participation of big businesses have created the perfect conditions for consolidating Russian agriculture’s position on the global market. And this integration is likely to go at an even faster rate than in other industries.

Naturally, if one starts from a growth rate of zero the figure is always higher, but the zero point has long been surpassed in Russia’s rural areas. To be even more precise, it never actually existed as Russian agriculture was not trapped behind the Iron Curtain during the Soviet era. Trade with the West continued in this sector, otherwise the country would have simply risked starvation.

According to the Federal Customs Service data from January-August, 2010, $22.18 billion in foodstuffs and agricultural raw materials were imported to Russia. This figure is up 21.4% compared to the same period in 2009, when imports amounted to $18.27 billion.

The volume of imported meat, milk, butter, citrus, coffee, tea, wheat, raw sugar and various other products increased by 15–20%, and by even more for some items. Poultry imports fell by 150% – indicating that there is a real alternative to “Bush legs” (imported American chicken) – and cereal, meat product and canned goods imports decreased as well. In parallel, foodstuff and agricultural raw material exports from January–August, 2010 amounted to $6.58 billion – which is 4.3% higher than in 2009 – while Russian wheat exports have increased by 17.4% and vodka exports rose to 36.6%.

Russia’s agriculture, which stagnated during the first years of reform, seems to be beginning to move forward. Administrative pressure on big business structure is already yielding initial results as entire sub sectors, with dairy and poultry farming in the lead, actually reached a level of sustainable competitiveness. If agricultural production is provided guidance in terms of basic organisation - primarily in resolving ownership issues - the investment boom here is almost inevitable. And should that happen, Russian agriculture may suddenly go from lagging behind to leading the country's economy – and this is no fantasy but rather a realistic assessment of agro industry capacity based on both Russian and foreign expert opinions.

This was further confirmed when American firm PepsiCo recently acquired 66% of one of Russia’s largest dairy producers, the Wimm-Bill-Dann company. The arrival of large investors will require the Russian government to revise its internal policies. President Medvedev described the investment climate in Russia as being “bad” in late December, 2010. At this point in time, Western investors do not feel confident enough to work in Russia for reasons stemming from the lack of security in doing business there and conditions imposed by Russian legislation as well. However, the Kremlin understands that without international cooperation, reviving Russian agriculture will be very difficult and the nation is likely to adopt a friendlier attitude towards foreign investors in the near future.

Russia’s position as a transit hub between Europe and Asia opens interesting prospects for foreign investors, primarily those from the United States. Transferring production and processing to Russian territory could become a viable option to the Asian region, which has been developed by big investors for a long time now. Aside from the relatively cheap and skilled labour force, Russia undoubtedly presents serious advantages over Asia in areas including hygiene, ecology and the availability of large areas for immediate use as well as the presence of a large domestic market.

Russia, on the other hand, is extremely interested in obtaining new Western agricultural technologies. Therefore, the world’s largest country has every chance of becoming a base for foreign companies and industrial processing as well as a springboard for penetrating new markets, all of which should have a positive impact on Russian agribusiness. Developing Russian agriculture can currently go two ways. The first option entails cooperation between major Russian business and foreign investment companies capable of providing Russia with new technology and considerable funds, thereby generating the means for investing in farms.

About 30% of Russia’s farmed lands in populated areas are already held by large landowners. However, the first option can hinder the second alternative for developing Russia’s agricultural business – which consists of supporting medium and small businesses in order to strengthen the continually weak status of Russian farmers.

The consistent failure of Russia’s rural areas was in fact an ongoing issue throughout the 20th Century; a problem which started with Soviet collectivization and expropriation of Kulak lands, continued through the mechanical enlargement of rural households in the 70s and the decline of manufacturing in the 90s. So it is crucial that the budding but fragile efforts at farming in Russia which have sprouted up over the past two decades not be crushed. A positive factor in farming development is the relatively low cost of land – particularly in the Siberian regions – which allows young people to acquire of land and create a farming business. This positive aspect distinguishes Russia from areas such as Western Europe, where in many cases young people cannot afford the substantial cost of purchasing a medium-sized farm, which is generally valued at several million euros. Attracting foreign investment and technology, combined with support and legislative protection for Russian farmers, may be the optimal solution for Russia’s rural areas. In any case, Russia should be ready to face the inevitable, world wide changes to come during the 21st Century. Russia already has all the essential elements to become a superpower as a global food supplier in the near future.